La hora gringa

The weekend has arrived and it’s time to make plans.

“I’ll see you at 7,” I say in Spanish to my friend over the phone, “Hora gringa, not hora peruana.”

“7, hora gringa,” he repeats, now well-versed in my need for a timely arrival.

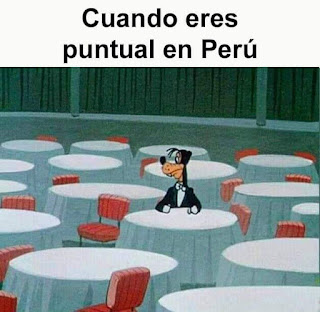

Time flies differently here in Peru, or rather, it crawls. Hora peruana is a phrase that existed long before JVs arrived in Tacna. It means that you can set a time for a meeting and expect people to arrive anywhere between fifteen minutes to an hour later than the appointed time. Here, someone might show up half hour late to a session or meeting and walk in as if they have arrived right on time.

I look at time through the uptight lens of someone who grew up in the United States, where people clock in to the 00:00:00 second at their workplaces. In the theatre world, I was taught fifteen minutes early was on time, on time was late, and late was fired. I lived by the tick of the second-hand on the clock in college, running from work, to class, to rehearsal and back again, berating myself if I arrived even five minutes tardy.

My Peruvian counterparts will often give me a hard time, knowing that time drives me crazy. When I first arrived in Tacna, the passing of time felt less like the sands of grain falling in an hour glass and more like the slow, torturous trickle of an icicle melting. I suffered endlessly in my first year as a JV, showing up fifteen minutes early to meetings that would sometimes be postponed by an hour or two, or even cancelled at the appointed time because so few participants had arrived.

Our closest Peruvian friends are now experts in the time difference. They know if we say “hora gringa” for 7 o’clock, they’ll have a window of about ten minutes before we start scolding them. Some friends have adapted to our need for timeliness so well that they often arrive before we do, teasing us for in turn falling prey to la hora peruana.

“Estoy yendo”

“Estoy bajando ahorita”

“Cinco minutos”

“I’m on my way, I’m coming down, five minutes.”

I often hear Peruvians tell me these phrases over the phone, both of us knowing full well that they have

a) yet to leave the house

b) yet to get on the bus or flag a taxi,

and that there is

c) no earthly possibility that their thirty minute bus ride will magically shorten itself.

If I were to describe the nature of time in the US as compared to Peru, I would guess that Americans see time as a long, linear path, with a finite end. We run around each day, making sure to check every box on our checklist, that fear of a final ending shaping our daily lives even if we like to believe otherwise. We think of the future and how the step we take now will affect the next steps, and so on. I would guess Peruvians would not describe time in a singular shape. The events of the day are thrown about, as if in a scatter plot. Plans can mold and stretch and change in a single minute. Such varied views have been shaped by the path of each country's history. It is rather easy to connect the strict, puritanical origins of the United States with our current, frenzied march around the clock. Likewise, Peruvian adaptability is reflected in the history of the country’s instability: for years under the control of foreign conquerers and then finally independent, only to fall into years of terror with the presence of the sendero luminoso. What might seem to me today like a frustrating lack of structure, was originally a way for a people to adapt to an unknown and dangerous future.

Nowadays, Peruvian timeliness is less of a mode of survival and more a way of life. And my own understanding of time has changed as well the longer I have lived in Tacna. Where I once dreaded every meeting and the long wait for its eventual start, I have finally begun to see the beauty in letting go of time. Waiting around means you start shooting the breeze with co-workers and students alike. A casual conversation might lead to an interesting revelation about a person’s background. Sometimes a casual question about someone’s father can lead to the story of one family’s migration across Peru. While I have waited with students, I have had the chance to see them let their guard down, to share with me dreams and worries that they carry around each day and have perhaps not yet had the time to share with anyone else. While "waiting", I have watched sunsets and seen parades go by. I have discovered a chance to breathe in and out, and even forget that I am waiting for something to begin.

As the countdown of my time here in Peru begins to tick closer and closer to the end, I use this gift of time to revel in each moment I am given. I look at the faces around me and celebrate the beauty of these two years spent abroad so far from home, in the company of new family and friends.

¡Ay, mi Camila! Me encanta tu reflexión acerca del tiempo y su flexibilidad en el Perú y en muchos países latinoamericanos. No sé si sabes la historia de cuando Abuela Shuba hizo una invitación a una fiesta en su casa en Davis. Invitó a los amigos gringos a las 9:00 pm y a los amigos colombianos a las 7:00 pm, para que así todos llegaran al tiempo. Pero, pasó lo siguiente. Una amiga colombiana que seguía las normas de tiempo gringo, llegó a las 7:00 pm a la casa de Abuela Shuba. Basta decir, que ninguno de nosotros estábamos listos y hasta todavía estábamos en la ducha o tratando de alistarnos para la fiesta. ¡Nunca se sabe!

ReplyDelete